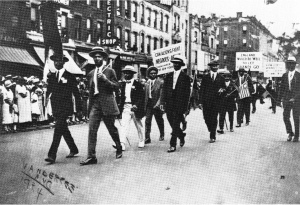

Harlem is also a parade ground. During the warmer months of the year no Sunday passes without several parades. There are brass bands, marchers in resplendent regalia, and high dignitaries with gorgeous insignia riding in automobiles. Almost any excuse for parading is sufficient — the funeral of a member of the lodge, the laying of a corner stone, the annual sermon to the order, or just a general desire to “turn out….[G]enerally these parades are lively and add greatly to the movement, colour and gaiety of Harlem” (James Weldon Johnson, Black Manhattan (1930), 168)

Parades also represented moments when blacks claimed the neighborhood’s streets for themselves, displacing the whites who drove the buses, trams, and taxis which traversed Harlem’s streets as well as most of the private cars. A few parades were major events, beginning outside the neighborhood, where the audiences were largely whites, and drawing huge crowds once they entered Harlem. Most parades remained within the neighborhood, attracting small groups of curious onlookers. The frequency with which they occurred was testimony to the strength of the rich fabric of voluntary groups, institutions and organizations that sustained life in Harlem.

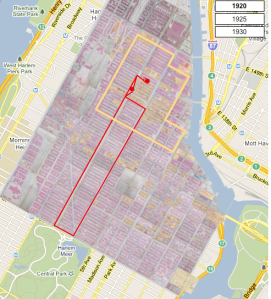

It is a parade that is most commonly invoked to mark the beginning of a new era for black Americans in the aftermath of World War One: the return of the 369th Regiment in 1919. That parade was one of the few that literally marched through Harlem, starting at 61st Street, and proceeding up 5th Avenue, across 110th Street, and up Lenox Avenue.

Black soldiers reappeared on the streets annually in the subsequent decade, as the 369th departed for their summer camps by parading from their armory at 143rd Street to the train depot/station at East 125th, and then returned two weeks later. Generally the regiment paraded on 7th or Lenox Avenues; in 1930, they marched down 5th Avenue, disappointing crowds waiting for them on Lenox.

Processions of lodge members, not marching soldiers are what Johnson evoked in his description of Harlem’s parades; they were the groups that most frequently took to Harlem’s streets. The Elks produced the largest parade of the decade, when Harlem hosted their national convention in July 1927. On that occasion, 25,000 men and women marched in pouring rain, following a route from 60th Street up 5th Avenue, then up Lenox Avenue, before crossing to 7th Avenue to go through the neighborhood (that the Elks did not march up Lenox as the 369th Regiment had in 1919 reflected that 7th had become Harlem’s main street by 1927). A platoon of mounted police, followed by a car containing James Blondy Brown, grand marshal, and Casper Holstein, honorary chairman of the local entertaining committee, led the parade, followed by the hosts, the Manhattan, Imperial and Monarch Lodges, and twenty-eight bands, including four female bands.

Fraternal lodges also held smaller parades to mark their anniversaries, marching from their lodges to local churches, participated in parades for the groundbreaking of churches, and to mark holidays such as July 4th; in 1929, Holstein led the Monarch lodge through the neighborhood up Lenox Avenue and down 7th Avenue, before crossing 135th St to St Nicholas Park.

Johnson’s description applied equally well to the parades of another group, Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Although they occurred only once a year, as part of the organization’s convention or anniversary, the UNIA’s parades were Harlem’s most photographed.

What drew the cameras was a combination of spectacle and controversy. Led by an ornately garbed Garvey — or, after his deportation, by a large photograph of their leader — UNIA parades displayed a combination of military and fraternal elements, including bands and ranks of men and women in the uniforms of the African Legion, Black Cross Nurses, Motor Corps, Juvenile Division and Marching Band, military attire more like that of the 369th Regiment than that worn by members of fraternal orders. Those UNIA members not in uniform carried placards adorned with slogans such as “Scattered Africa unite” and “The Negro Won the war,” which in expressing the often controversial positions that Garvey took throughout the 1920s gave these processions a political character. Automobiles, buses and floats also featured in the parades

When the UNIA took to the streets in the early 1920s, it also typically ventured further south than fraternal organizations, out of black Harlem into blocks populated by whites, to 125th Street on the occasion of its first convention in 1920, and as far south as 110th Street in 1922 and 1924.

When the parade for the 1922 convention crossed into the area occupied by whites, according to a report in the New York World, banners appeared reading, “White man rules America, black man shall rule Africa,” “We want a black civilization,” and “God and Negro Shall Triumph.” (For more, see the post on the UNIA in Harlem)

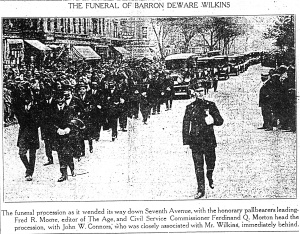

The final group of parades, those for funerals, were far smaller than those consisting of soldiers or celebrating the anniversaries or activities of organizations. Funeral processions also followed shorter routes, bearing the coffin from the undertakers to the site of the funeral, and then out of Harlem for burial, usually in Woodlawn cemetery in the Bronx.

As Johnson noted, the typical parade came on the death of a lodge member. Such parades drew few onlookers, unless that member had attained some degree of celebrity or notoriety, when large crowds could come out, as they did for the funeral of Barron Wilkins, a cabaret owner and sporting identity who was also a member of the Monarch Lodge of the Elks. The funeral procession that drew by far the largest crowd of any that occurred in Harlem was for one of the neighborhood’s true celebrities, singer Florence Mills, when somewhere over 150,000 packed the streets.

While the crowds might have differed, funeral parades themselves took essentially the same form. Pallbearers took the lead, as is the photo of Wilkins’ funeral, followed by the hearse and other vehicles. Bands from lodges also often formed part of the procession, as they did in Mills’ funeral.

[…] spectacle for black residents and their neighbors in the blocks further south (for details, see the post on Parades; there is only sufficient evidence to map the routes of the 1922 and 1924 […]

[…] His first appearance above Harlem occurred during the 1922 UNIA Convention, when he flew over the parade in a plane decorated with UNIA slogans. That flight led to his appointment as head of the […]

I’m looking for photos of the UNIA, as part of a documentary project. I am wondering where you got your photos and how to get in contact with anyone who has similar photos.

The sources of all the photos are identified in the blog posts, and in many cases the photos link to their source. I’m sure you’re already in touch with the Garvey papers folk at UCLA, which is where many of the photos come from. James Van Der Zee took many of the most interesting photographs, and by all accounts his widow Donna Mussenden Van Der Zee is still in possession of many images

[…] it is noteworthy that in 1936 on a balmy April evening, an impeccable 65-piece brass band from the Monarch Lodge of the Fraternal Benevolent and Protective Order of the Elks marshaled a jubilant crowd of 10,000 fans into the streets outside of a Harlem theater to celebrate […]

[…] Organizations paraded along those streets; the Elks convention in 1927 involved the largest parade of the 1920s, featuring 25,000 men and women (in pouring rain). Visitors filled the pavements, and […]