(For more description of daily, weekly and seasonal patterns of everyday life in Harlem, see Constrained but not contained: Patterns of everyday life and the limits of segregation in 1920s Harlem)

West 125th Street is now perceived to be the heart of black Harlem, but in the 1920s there were more whites than blacks on that thoroughfare. You had to travel 10 blocks, or one subway stop, further north to find the unbroken sea of black faces that signified Harlem. The first building given over to black tenants, in 1903, stood on West 134th Street, and it was from that hub that subsequent waves of migrants from the South and immigrants from the West Indies pushed out the boundaries of black settlement.

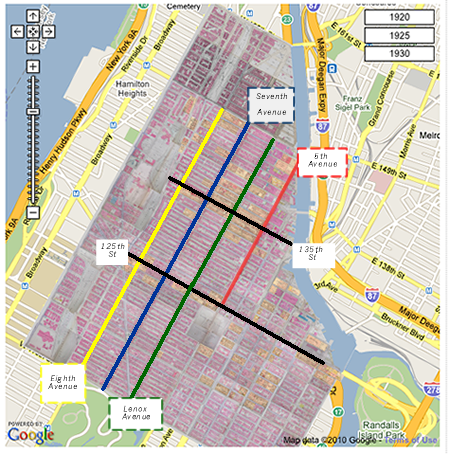

In 1920, the area occupied entirely by blacks stretched from 130th Street to 144th Street and Fifth Avenue to Eighth Avenue, an area of forty-eight blocks that was home to 73, 000 people. Five years later, black Harlem reached south to 128th Street, and, below 135th Street, east to Park Avenue. By 1930, blacks, now numbering over 200,000, almost one fifth of whom hailed from the West Indies, had spilled over Eighth Avenue to Amsterdam Avenue and the heights overlooking central Harlem as far south as 130th Street, moved north to 160th Street, and had begun to settle as far south as 110th Street, where their neighbors were not white, but Spanish-speakers from Puerto Rico and the Caribbean.

If the influx of southerners and West Indians made this district black, they did not render it a homogenous place. In addition to the areas in which better-off blacks made their homes, Strivers Row on West 139th Street and, late in the 1920s, Sugar Hill on Edgecombe Avenue, there were other distinctive neighbourhoods in Harlem.

Climbing the stairs from the 135th Street subway station brought you to Lenox Avenue. Crowded, dirty and noisy, the avenue was the site of the Savoy Ballroom and Harlem Hospital, but otherwise its businesses were small and less reputable. To the east, the blocks between Lenox and Fifth Avenues were among the most densely packed residential streets in the entire city, tenement buildings where many families took in lodgers to help pay the rent. All Harlem’s cross streets other than 135th Street shared this solidly residential character, if not the population density or the tenement buildings. That did not mean they were indistinguishable. It was on these streets that black churches and fraternal organizations made their homes. Migrants and immigrants also clustered together; the tenants in particular buildings came predominantly from the West Indies, or from Georgia or North Carolina or Virginia. The streets east of Lenox Avenue that had the poorest housing, between 127th Street and 135th Street, were also home to the densest clusters of prostitutes.

If you exited the subway to the west, and walked past the businesses located below the apartments on 135th Street, and the landmark YMCA building, you came to Seventh Avenue. Christened the ‘Black Broadway’ by writer Wallace Thurman, the wide avenue was Harlem’s main street, along which could be found its best stores, theaters and churches, past which flowed a constant stream of black New Yorkers frequenting those sites or simply promenading along the broad pavements. In the mornings, numbers runners could be found on almost every corner, and the length of Lenox and Eighth Avenues, collecting bets for the game that permeated Harlem life and represented the neighborhood’s largest black enterprise. Later in the day, street speakers could be found on the corners. If you stepped off the street, however, the sea of black faces broke on the store counters; whites owned and staffed almost all of Harlem’s businesses. Most black enterprises were not to be found in the district’s storefronts, but in its apartments, where women operated beauty salons and nurseries.

During the summer, blacks took to 7th Avenue itself, in parades of church groups, fraternal organizations, the local 369th Regiment, and, most spectacularly, the Universal Negro Improvement Association, Marcus Garvey’s black nationalist organization, which had both its headquarters and conventions in Harlem. At other times, the street proved dangerous: in the mid-1920s, an average of almost ten people a day, including two children, suffered injuries in automobile accidents, most on or near Seventh or Lenox Avenues, which were major routes out of the city. The frequency with which children were hit by traffic reflected the lack of playgrounds in Harlem, which led them to play on the neighborhood’s streets when they were out of school.

Continuing west brought you to Eighth Avenue, shrouded in dirt, noise and shadow by the elevated train line that ran its length, a street, as Thurman put it, “to cross hurriedly in order to reach places located east of it.” The relative lack of crowds allowed the avenue to become the home to Harlem’s street markets; originally on Lenox Avenue, by the 1920s they could be found under the elevated train lines from 139th to 145th Streets. By 1930, as the areas around Eighth Avenue became more solidly populated by blacks, the street’s corners attracted increased numbers of prostitutes playing their trade.

The boundaries of black settlement in Harlem did not contain the lives of residents. Work almost always required blacks to leave Harlem, with the manual labor as longshoremen, janitors, elevator and switchboard operators, porters, day laborers, and waiters to which discrimination by whites restricted black men taking them to different parts of the city than did women’s work as domestic and personal service, as laundresses, hairdressers, domestic day workers (general housework and laundry), and maids. Residents also left Harlem for leisure, particularly on Sundays to watch baseball and cricket, or on Saturday evenings to watch basketball and boxing. In summer, they journeyed to Rockaway beach, or further afield to summer camps, or to camp with the 369th Regiment.

I like this

[…] Harlem in the 1920s […]

How many blacks owned the buildings/businesses?

Only about 20% of the businesses in Harlem were owned by blacks

[…] when the Regent had just opened, Seventh Avenue was becoming known as “Black Broadway”. The area which had seen a massive influx of African Americans after WWI was only slowly waking up […]

why many black men didn’t own anything at the roaring 20’s

Thanks for the great info on Harlem in the twenties. Good souce for info for a book I am writing. Elizabeth Quigley

[…] [8] 1920 Census; Sarah Barber Head – Manhattan Assembly District 13, New York, New York; Roll: T625_1209; Page: 24A; Enumeration District: 958.[9] Internet: Digital Harlem Blog –“Harlem in the 1920s” […]